You’ve probably heard the term 'jet stream' before — perhaps in one of our forecasts or mentioned in the media. Over the last few years this atmospheric feature gained popularity quickly, which is justified when looking at the jet’s influence on the weather we experience daily. In this article you will find out how the atmosphere behaves in the vicinity of the jet stream and how it is able to fuel dangerous autumn storms.

The basics

Before getting into the details on how the jet stream affects the ambient atmosphere we need to dive into the underlying drivers; principles which allow the exceptionally high wind speeds, associated with the jet, to occur in first place. As with most weather phenomena, temperature differences (and associated pressure perturbations) are the main engine. In an attempt to balance out these differences the air starts to move around. On a rather small scale you can think of land-sea circulations, convection and katabatic winds for example. The physics also apply on a planetary scale; with vast circulations developing between the tropics, mid-latitudes and poles as a result of the ever-present temperature gradients between these regions.

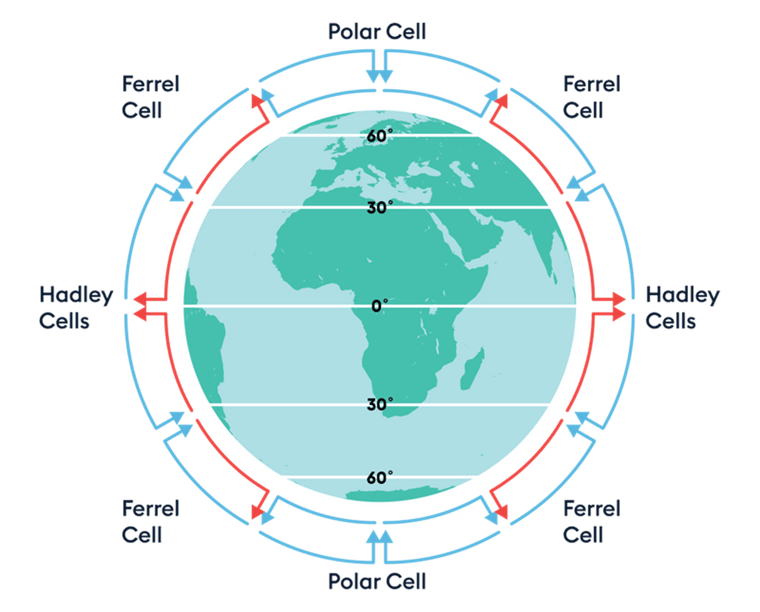

Globally we encounter three circulation cells, both in the northern and southern hemisphere; the Hadley, Ferrel and Polar cell. See figure 1 below. All contain a different airmass with other characteristics, ranging from (sub) tropical near the equator to polar and eventually arctic near the poles. The rising and sinking branches are linked to differential warming (rising) and cooling (sinking) of the air particles. Right in between the cells temperature- and pressure gradients are well-developed, enabling elongated bands of winds to develop in the higher regions of the troposphere; the jet stream.

Figure 1. Different circulation cells surrounding the planet. Source: EncounterEdu.com

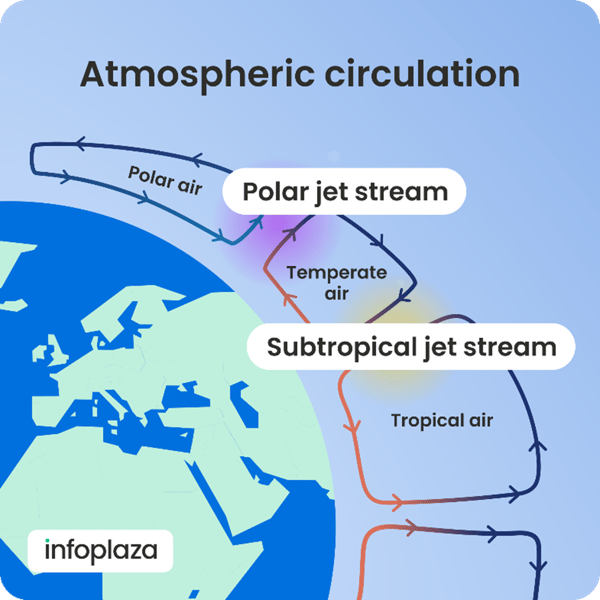

We can distinguish two main jets: the polar and subtropical jet stream, present near 50-60° and roughly 30° respectively. Both wrap around the planet in an undulating fashion and can be considered as very important atmospheric features, behaving like vast conveyor belts transporting large weather systems. See figure 2. Jet streams tend to ‘follow the sun’, meaning that they move north and south with the varying seasons. On both hemispheres highest wind speeds are recorded during winter, when temperature differences between pole and equator are maximized.

Figure 2. Placement of the two main jet streams between circulation cells

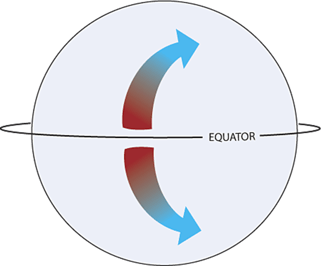

You might wonder why there’s not simply one cell spanning the entire distance from the equator to the poles. In the end that would have been much more efficient. Aforementioned differential heating and cooling, as well as conservation of angular momentum (also known as the Coriolis force) are generally responsible for the splitting of the circulation into separate cells.

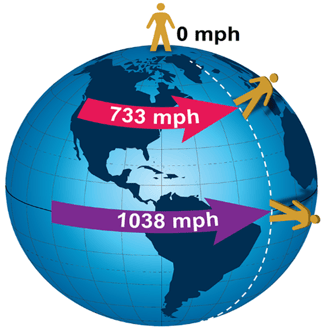

For example; an air particle rising in the upward branch of the Hadley cell near the equator will be transported poleward whilst maintaining its initial momentum (which is highest at the equator, see figure 3 and 4 below). As our planet spins eastward this conservation of angular momentum causes it to follow a deviating path to the east, instead of straight towards the poles. This happens both in the northern and southern hemisphere, causing a westerly airflow in the upper troposphere between the different circulation cells. Hence, the Earth’s rotational speed is also one of the cradling principles of the jet. The arising Coriolis force (which actually is an apparent deflection) impacts the air particles and causes an overall push to the east.

|

|

Figure 3 (left), and 4 (right). For air moving poleward conservation of angular momentum will cause an eastward deviation aloft, both in the northern and southern hemisphere. Source left and right image: NOAA

So what?

We now know that the jet stream is an undulating band of strong winds (sometimes reaching speeds over 200 kt) present in the upper troposphere, on average around 10km AMSL. It’s easy to think that at such an altitude the impact on the weather near the surface is minimal, but nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the jet stream can create very explosive settings in which areas of low pressure deepen explosively, yielding devastating winds, especially during autumn and winter. To understand these dynamics, we need to dissect the jet and look at its internal workings more closely.

The strength of any wind maximum is usually determined by the tightness of the temperature and pressure gradient along which it develops. The more pronounced these gradients are the stronger the winds coming forth. Keeping this in mind it’s easy to imagine that the windspeed along the entire jet stream is far from homogeneous.

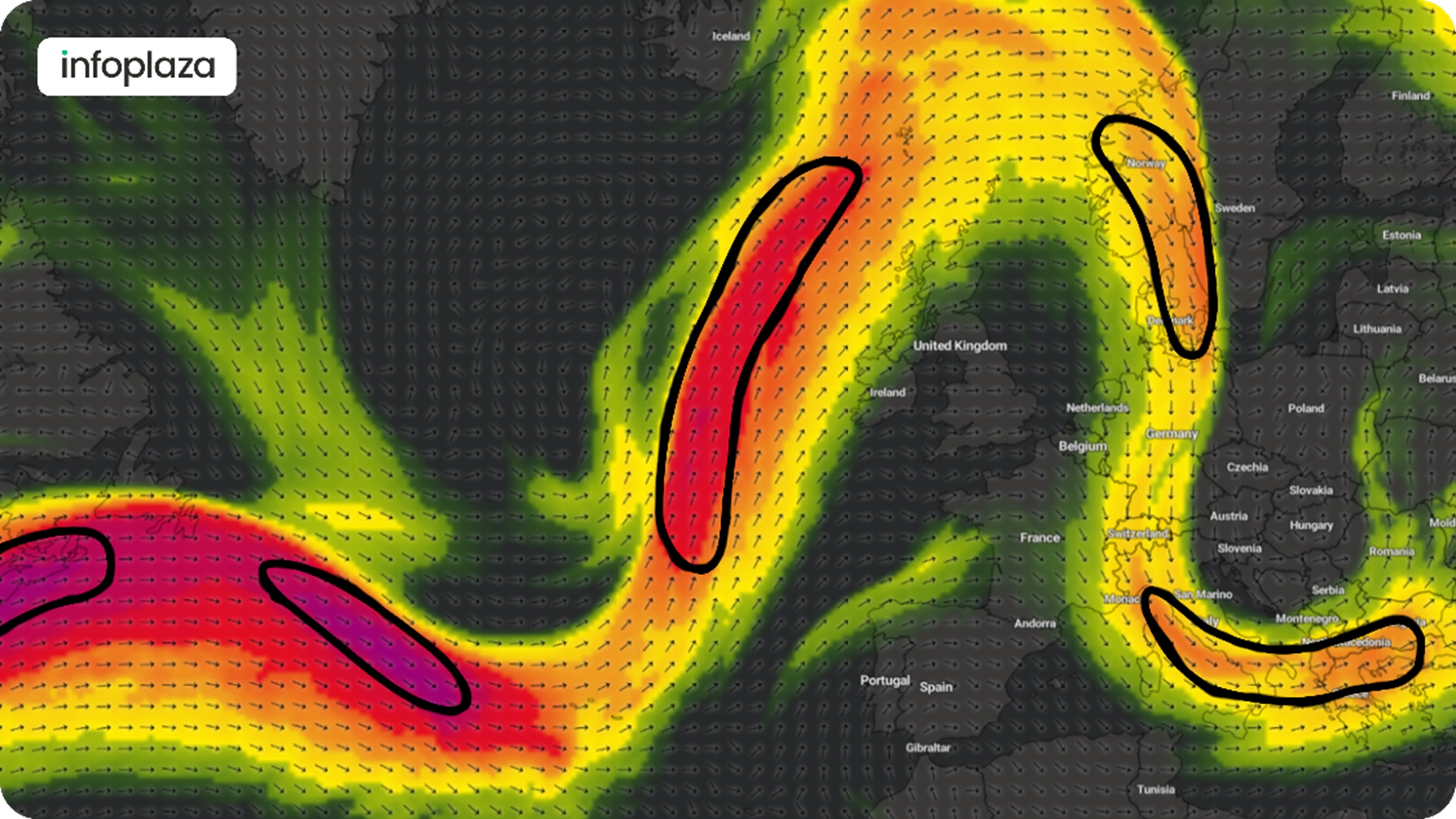

Zones with wind maxima are usually alternated by weaker areas (see figure 5 below). In the latter case strong undulation can take place, while in the case of a strong jet little to virtually no bending takes place. Even though it seems of limited importance at first sight, the areas with high wind speeds are especially conducive for the development of severe weather. These so-called ‘jet streaks’ are one of the main focal points for our meteorologists when it comes to making your maritime forecast.

Figure 5: Jet stream undulating over the Atlantic and western Europe, with highlighted jet streaks. Source: I’m weather/ECMWF)

For the development of autumn and winter storms we usually focus on the interactions taking place along the entrance and exit regions of these jet streaks. To see how this works we need to look more closely at how air particles react to acceleration when entering the streak and slowing down again when leaving. See figure 6.

When an air particle enters the jet streak its speed will significantly increase over a short period of time. This means that the forces impacting the particle are altered as well. Simplified; in this case the pressure gradient force, as well as gravitational force, will become predominant upon entering the streak. The Coriolis force is greatly linked to speed and tends to affect the particle with a slight delay, leading to a net deviation towards the cold side of the jet streak. An opposite movement takes place when air leaves the streak, leading to a gradual transition towards the warm side of the jet. Air particles outside the streak will not be impacted and travel in a straight-lined manner, which leads to an accumulation or ‘shortage’ of air along the different entrance and exit regions of the streak.

Figure 6. Animated airflow through a jet streak. Notice the deviating path of the air particles crossing the streak.

Shortage regions resemble upper air divergence and (strong) upward motion as the air below rushes upward to replenish the ‘missing’ air. At the same time regions with a surplus of air encounter sinking motions (subsidence). The left exit and right entrance are focal points for possible severe weather as upward motion is fueled here, especially when an overlap with low- and midlevel weather systems is realized.

Severe disruptions of maritime operations

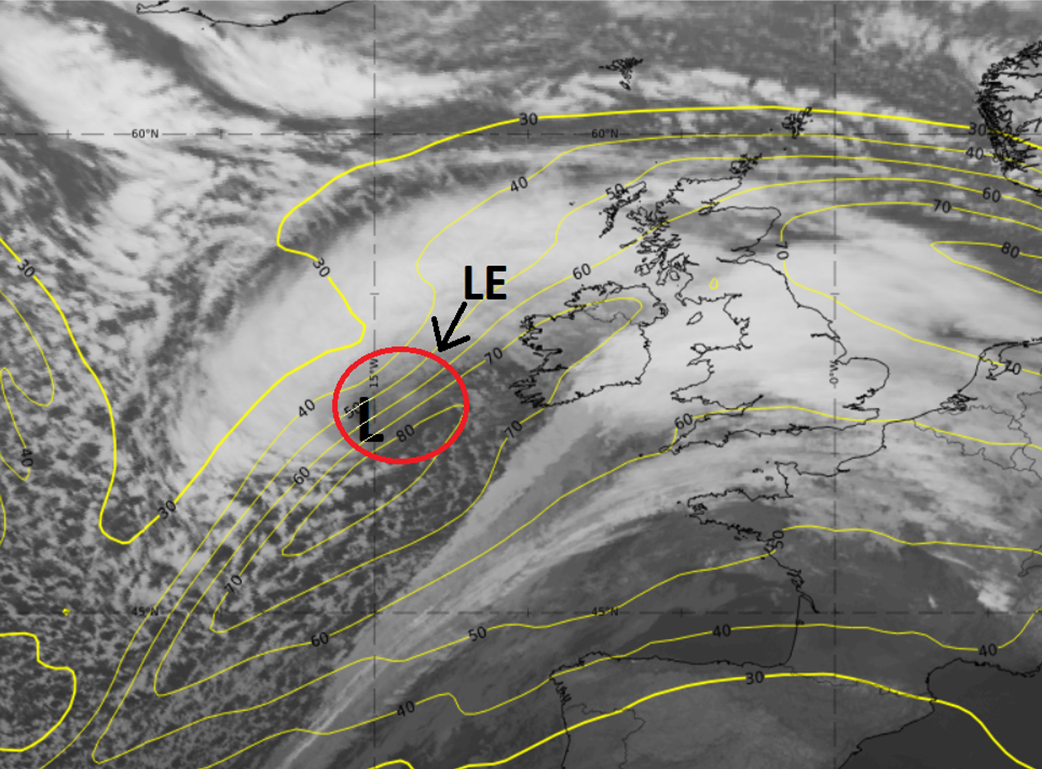

Luckily, being positioned directly under one of the rising branches of the jet stream’s circulation doesn’t happen that often as they are rather small and move around fairly quickly. But when juvenile lows cross the jet-axis, and shortly interact with the left exit for example, rapid cyclogenesis can take place. This process of extremely fast deepening often leads to quick development (6-12h) of classic autumn storms with long swaths of devastating winds, high waves and life-threatening situations offshore. In these situations, a short-lived deep coupling between the surface and the jet stream exists, with highly effective up- and downward chimney-like abduction of air. Even when this interaction isn’t optimized, the presence of a strong jet will inevitably lead to a prolonged period of unsettled weather over a much larger area than just the upward branches.

Figure 7. On February 17th 2022 a very powerful storm rapidly deepens over the Atlantic under the left exit of the jet stream. Lines of equal wind speed aloft (isotachs, 300hPa) depicted in yellow, location of the left exit (LE) in the red circle, and the storm’s center in black (L). The system carries the name Eunice and is till this day one of the strongest storms ever recorded with gusts exceeding 200km/h offshore. Source IR satellite and model data: Eumetrain/ECMWF

The left exit, as well as the right entrance of the jet, are also notorious for their ability to facilitate deep convection when interacting with unstable air. This might lead to organized thunderstorms with severe gusts.

How we deal with the jet stream

In the weather room of Infoplaza our meteorologists are always aware of the jet stream’s position and its potential impact on underlying weather systems. They are always on the lookout for low pressure areas, internally called ‘jet crossers’, as they occasionally develop into malicious systems.As with most impactful weather events, timing is of the essence. We understand that taking preemptive measures in order to keep people and material safe, before a storm hits, is of high importance to you. Specialized in analyzing complex weather patterns, not only on the short term but also up to a few weeks ahead, we can contribute to your operational safety offshore. As always, guiding you to the decision point.

Are you curious about whether our services can contribute to the success of your operations? Feel free to contact us at any time.

.png?width=360&name=nasa-goes-earth-doldrums-00_0%20(1).png)